As Avatar Singh, the first Indian judoka to qualify for the Olympics in over a decade, prepares to go to Rio, a look at the country’s fascinating introduction to the martial art.

Written by Murali K Menon | Published:July 3, 2016 12:01 am

In 1934, Subimal Ray, Satyajit Ray’s youngest uncle, decided that he really had to learn judo, and took his nephew along with him to meet the great sensei Shinzo Takagaki. The duo caught a tram to Takagaki’s home in Swinhoe Street, Ballygunge, Calcutta, and apprenticed themselves to the master judoka. In his Childhood Days: A Memoir, Ray writes, “We began our lessons when our costumes were ready… Forty-five years later, I can recall only two intricate holds: sheoi-nage and nippon-shio. Two other gentlemen used to join us on the days we visited Takagaki. One of them was a Bengali and a trainee, like ourselves. The other was an Englishman, an army man called Captain Hughes, who lived in Fort William. He was a light heavyweight boxing champion in Calcutta… He already knew judo. He came to Takagaki simply to practice what he had learnt, for there was no one else in Calcutta to rival him. Their fights were always extraordinary affairs. We used to watch them, spellbound.”

To learn that one of the world’s greatest filmmakers was, at least in his younger days, a martial arts enthusiast might bring a felicitous smile to one’s face — it also explains Feluda’s proficiency in judo — but what was this guy, Takagaki, considered to be the father of judo in Asia, doing in Calcutta in the 1930s? The answer to that question is an unlikely one, and you have to be a committed judoka of a certain vintage to be aware of it. Shinzo Takagaki came to Bengal, or, more specifically, Santiniketan, in 1929 on the invitation of Rabindranath Tagore.

“Tagore was a great admirer of Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo. In fact, a jiu-jitsu teacher (judo is derived from jiu-jitsu) Jinnosuke Sano taught students at Santiniketan as far back as 1905,” says Cawas Billimoria, a 10-time national champion and Olympian. Billimoria is, at present, mentoring Avatar Singh, who, earlier this month, became the first Indian judoka in over a decade to qualify for the Olympics.

According to John Stevens’s The Way of Judo: A Portrait of Jigoro Kano and His Students, the dojo at Santiniketan trained girls and boys together, “something unheard of in India at the time”, and one of Takagaki’s students was Amita Sen, mother of the economist Amartya.

Tagore visited Japan numerous times — and the Kodokan, the global judo HQ, in Tokyo, in 1929 — and his interest in judo was possibly an extension of his infatuation with Japanese culture. (It is said that he celebrated Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 by lighting bonfires around his home. His fondness for the country and its people, though, faded as Japan’s imperialistic designs on Asia and the world became increasingly clear.)

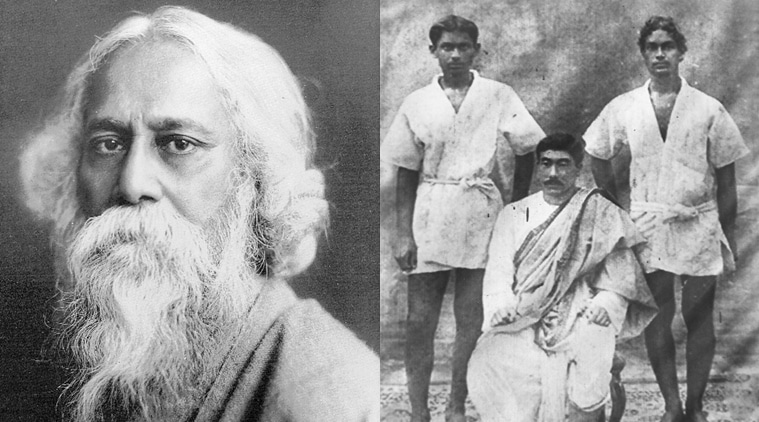

Rabindranath Tagore (L) was a great admirer of Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo, a 1905 photo of Japanese jiu-jitsu teacher Sanosan (seated) with Tagore’s son, Rothindranath (standing, right) and Santosh Chandra Majumdar.

Rabindranath Tagore (L) was a great admirer of Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo, a 1905 photo of Japanese jiu-jitsu teacher Sanosan (seated) with Tagore’s son, Rothindranath (standing, right) and Santosh Chandra Majumdar.

While Tagore was a pacifist and ambivalent about nationalism — a dangerous position to take in today’s times — judo fitted right in, at least during its initial years, in Bengal at the turn of the last century.

The early 1900s were incendiary times in Bengal, when nationalism acquired a muscular profile. The British, who were masters at cultural emasculation, had for long stereotyped the Bengali male as “effete”. Thomas Macaulay wrote that: “Whatever the Bengali does, he does languidly. His favourite pursuits are sedentary. He shrinks from bodily exertion; and though voluble in dispute… he seldom engages in personal conflict, and scarcely ever enlists as a soldier. There never perhaps existed a people so thoroughly fitted by habit to a foreign yoke.”

Exhorted by the likes of Swami Vivekananda and Aurobindo Ghose, the men of Bengal plunged into physical culture, and so strong was the interest in bodybuilding that when the Prussian Eugen Sandow, the man who invented modern bodybuilding, visited Calcutta in 1904, he was afforded a rockstar’s reception at Howrah Station.

“Many of these new physical culturists allied themselves with revolutionary movements. Some joined gymnasiums and akharas, which served as a front for the extremist activities of organisations such as the Anushilan Samiti (literally, society for education of all faculties) and Jugantar, while others gravitated towards academies that taught martial arts indigenous to Bengal,” says Abhijit Gupta, who teaches English at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and is researching physical culture in colonial Bengal. One of these martial arts institutes was set up by Tagore’s niece, Sarala Devi Chaudhurani, and it wasn’t long before jiu-jitsu/judo caught the eye of the revolutionaries.

“Pulin Behari Das, who founded the revolutionary Dhaka Anushilan Samiti, secretly learnt jiu-jitsu techniques from Sano. Sano was a practitioner of a koryu budo form, and the photographs and illustrations we’ve seen of Das’s techniques bear remarkable similarity to techniques practised in modern day jiu-jitsu derivatives such as aikido. Das, who was a great stick-fighter and swordsman, synthesised Sano’s jiu-jitsu with various indigenous martial arts he had learned, and called it ‘Bharatiya jiu-jitsu,’” says Deeptanil Ray, a researcher at Jadavpur University’s School of Cultural Texts and Records. Ray co-edited the recently released Astracharcha, a compilation of Das’s writings and lifelong research on martial arts, including free-hand self-defence (jiu-jitsu).

Despite Tagore’s best efforts and repeated reminders to the Calcutta Municipal Corporation and its then mayors, including Subash Chandra Bose, to help him popularise the martial art among the youth, judo never attained the popularity bodybuilding did in the early decades of the 20th century in Bengal. But the tumult of those years did leave behind a legacy and birthed several men, who were the very antithesis of Macaulay’s view of the Bengali man. Many of India’s judo champs after Independence were from Bengal, and two of the country’s first Mr Universes, Monotosh Roy and Manohar Aich, who passed away recently, were both “low-lying people from a low-lying land with the intellect of a Greek and the grit of a rabbit.”

Source: http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/life-style/the-nippon-shio-of-rabindranath-tagore/

amazon viagra viagra without a doctor prescription viagra pills

switching from tamsulosin to cialis cialis online cialis erection penis

viagra 100mg viagra for sale where can i buy viagra

ed natural remedies the canadian drugstore online drugs

otc viagra generic viagra online over the counter viagra

viagra without a doctor prescription canada buy viagra online viagra amazon

generic viagra walmart viagra cheap generic viagra

best place to buy generic viagra online viagra cheap viagra online

how to buy viagra generic viagra online how to get viagra

buy online drugs ED Pills Without Doctor Prescription viagra without doctor prescription

best ed medications cheap ed pills best ed drugs

ed clinic Cheap Erection Pills medicines for ed

cialis 100 mg lowest price cheap cialis is cialis generic available

how to take cialis buy tadalafil online cialis

best ed treatments buy generic ed pills online treatment with drugs

ed medications list

new treatments for ed canadian drug pharmacy how to get prescription drugs without doctor

injectable ed drugs

ed pumps best canadian online pharmacy legal to buy prescription drugs without prescription

online ed pills

https://zithromaxgeneric500.com/ zithromax online usa no prescription

https://zithromaxgeneric500.com/ generic zithromax 500mg

dapoxetine 30mg india https://dapoxetine.confrancisyalgomas.com/

naltrexone side effects alcohol https://naltrexoneonline.confrancisyalgomas.com/

https://valtrexgeneric500.com/ buying valtrex

https://amoxicillingeneric500.com/ amoxicillin capsule 500mg price

payday loans no credit check instant approval personal loans with no credit check

online pharmacy buy generic drugs cheap tablets

chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine trials https://hhydroxychloroquine.com/

payday loans no credit check payday loans no credit check

vidalista 20mg https://vidalista.mlsmalta.com/

payday loans online fast deposit payday loans no credit check

buy generic drugs cheap tablets buy generic drugs online from india

how safe is generic ivermectin https://ivermectin.webbfenix.com/

vidalista super active difference https://vidalista.buszcentrum.com/

mexico silagra sold over counter https://silagra.buszcentrum.com/

hydroxychloroquine use in michigan https://hydroxychloroquine.mlsmalta.com/

ivermectin for rosacea reviews https://ivermectin.mlsmalta.com/

walgreens generic viagra price http://droga5.net/

best over the counter viagra viagra amazon viagra

dapoxetine in china pharmacy https://dapoxetine.bee-rich.com/

viagra pills

https://sildenafilxxl.com/

viagra coupons from pfizer

cheapest generic viagra https://sildenafilxxl.com/ generic for viagra

viagra vs cialis vs levitra

https://sildenafilxxl.com/

viagra vs cialis

anti fungal pills without prescription online canadian pharmacy best pill for ed

the happy family store https://edmeds.buszcentrum.com/

generic viagra walmart buy viagra online generic viagra

ed pills that work quickly buy Prednisone buy prescription drugs from canada

Good post. I certainly appreciate this website. Keep it up!

over the counter viagra

https://viagraproff.com/

viagra on line

generic viagra without a doctor prescription canadian online pharmacy drug prices comparison

generic cialis at walmart cialis tadalafil does cialis lower blood pressure

canadian pharmacy online generic Amoxil cat antibiotics without pet prescription

is cialis better than viagra https://tadalafili.com/

when will viagra be generic viagra prices viagra amazon

viagra price buy viagra viagra over the counter walmart

40mg vidalista daily effects https://vidalista40mg.mlsmalta.com/

ed pills for sale best canadian pharmacy ed tablets

viagra price how to get viagra without a doctor price of viagra

cheap medications buy Zithromax cheap online pharmacy

buy ed pills canadian pharmacy online how to treat ed

100mg viagra without a doctor prescription ed meds drug prices comparison

cialis cost in usa https://wisig.org/

doctor services online https://edmeds.buszcentrum.com/

i like this very good article

does dapoxetine cure ed https://ddapoxetine.com/

best medication for ed: causes for ed best ed medication

natural cure for ed: buy canadian drugs ed clinics

cheap asthma inhalers online https://amstyles.com/

car policy

hydroxychloroquine regimen for covid https://sale.azhydroxychloroquine.com/

anti fungal pills without prescription

pain medications without a prescription

prescription drugs without prior prescription

zithromax capsules australia can i buy zithromax online how much is zithromax 250 mg

buy cialis

the cost of cialis

cialis without a doctor’s prescription

bad credit installment loans guaranteed

virtual fuck

free cialis canadian cialis tiujana cialis

term life insurance price

canadian pharmacy mall

online pharmacy without scripts

zithromax 500mg price in india azithromycin zithromax zithromax buy online

cvs prescription prices without insurance

buy prescription drugs online legally

is it illegal to buy prescription drugs online

how to get viagra

viagra otc

viagra walmart

liberty mutual auto insurance quote

how much viagra should i take the first time? over the counter viagra is viagra over the counter

online pharmacy canada generic viagra

direct car insurance

over the counter viagra cvs viagra prices viagra without a doctor prescription canada

viagra for sale mail order viagra canadian pharmacy viagra

online viagra

when to take viagra

viagra alternatives

$200 cialis coupon

generic for cialis

30 day cialis trial offer

hoodia slim

installment loan

cialis paypal uk

zithromax 500 zithromax capsules australia zithromax over the counter canada

loan with no credit

viagra without a doctor prescription

prescription drugs online

levitra without a doctor prescription

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

You made some nice points there. I looked on the internet for the subject matter and found most individuals will agree with your site.

Your style is so unique compared to other folks I’ve read stuff from. I appreciate you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just bookmark this blog.

cheap pet meds without vet prescription

generic viagra canada women viagra

how much viagra should i take the first time? generic viagra canada cheapest viagra online

cheapest viagra online

discount viagra viagra without doctor prescription viagra without a doctor prescription usa

viagra online usa

ivermectin 3mg tab

viagra price in mexico

where can i buy viagra over the counter viagra for sale viagra online canadian pharmacy

price of viagra

comfortis without vet prescription

viagra generic for sale generic viagra available

homeowners insurance quotes comparison

buy prescription drugs from india

viagra generic for sale walmart viagra

buy generic viagra online india

viagra 100mg prices

best price for genuine viagra

bad credit loans direct

same day loans online

home insurance quotes online

homeowners

personal loan form

cheapest homeowners insurance

buy viagra online free shipping

augmentin 875 mg 125 mg tablet

indocin sr 75 mg

order kamagra usa

ciprofloxacin 500 mg coupon

levitra cost uk

generic cialis for women

viagra 100

flomax without prescription

prednisolone 25 mg price australia

onlinecanadianpharmacy

dapoxetine 30 mg tablet online purchase in india

viagra tablet price in india

ciprofloxacin medicine

doxycycline hyclate 100 mg

malegra 120

no prescription pharmacy paypal

levitra tablet buy online

erythromycin over the counter australia

cialis us pharmacy online

generic viagra online for sale

combivent inhaler price

viagra professional cheap

synthroid 75 mg

price of viagra in india

sildenafil 20 mg tablet

cheapest buspar

female viagra capsule

misoprostol 200mg

viagra pharmacy usa

cialis average cost

tadalafil 2.5 mg in india

rate online pharmacies

best price on cialis

cheap viagra online fast shipping

sky pharmacy

canadian pharmacy india

online pharmacy for sale

tadalafil tablets 20 mg buy

vermox tablets australia

super force viagra

brand name cialis for sale

tadalafil cheap

cialis australia

best us price tadalafil

provigil rx

top 10 pharmacies in india

cheap viagra online no prescription

cheap brand viagra

buy discount cialis

where to purchase cialis online

canadian pharmacy ed medications

hydroxychloroquine sulfate tablets

can you buy viagra in mexico

generic viagra canada paypal

propecia 5 mg for sale

sildenafil citrate tablets 100 mg

orlistat online pharmacy

doxycycline 50mg capsules

best pharmacy prices for viagra

viagra 100mg cost in india

levitra online order

online pharmacy uk viagra

cialis daily use coupon

order viagra online us

sildenafil 100mg price comparison

cheap viagra 50mg

order sildenafil from canada

buying viagra nz

best price viagra canada

tadalafil from india 5mg

cost of tadalafil 5mg

ivermectin canada

sildenafil generic 5mg

cialis cheapest lowest price

cialis everyday

tadalafil 100mg tablets

buy viagra online canada paypal

viagra cost usa

cost of sildenafil in mexico

cialis prescription cost

brand cialis online

prinivil lisinopril

ivermectin 4 mg

stromectol canada

how much is sildenafil 100mg

sildenafil buy online canada

cialis 10mg online

cialis .com

which online pharmacy is the best

india cialis generic

canadian pharmacy viagra cost

cost of viagra in india